What is it like to be intelligent?

Exploring the depths of human consciousness

Exploring the depths of human consciousness

Let me start by declaring my motivation for writing about a topic I have no explicit authority on. I’ve been writing for years by now, both on topics I work on with my companies, as well as topics that simply interest me. I find, personally, that writing is a powerful form of learning through synthesis. It’s easy to say you understand something until you have to explain it to someone else. It’s relatively easy to explain something in an elevator pitch format, but a lecture or blog post requires you to really think through structure, validity, and consistency. It forces you to find references to support your claims. Basically, it’s a great way to ensure you’re not fooling yourself through a series of simplifications and delusions. So I’m doing this more for me than you, but you can come along for the ride.

So, let’s talk about the C-word. Consciousness.

We all have rare moments in our life when we stop and ponder a big question. Is my blue the same as your blue? Why is the sky blue? Are there aliens out there? Is there an afterlife? What came before the big bang? What’s the end of the universe? What’s the meaning of it all?

Of course, some of these, science can answer. The sky is blue for the same reason oceans are blue, it is the shortest wavelength light we can still see with our eyes, and therefore scatters from particles in water and air over great distances and gradually dominates the other colors. Some questions we don’t have answers for yet. Some questions we probably never will.

While it’s easy to get caught up in our own minds and worlds, it can be helpful to take a step back and think about simple cases as sources for fundamental truth.

Have you ever… stopped to think about what it’s like to be a bat?

Not in the sense of flying per se, but in that do they even have an inner experience like we do? If there was such a thing as reincarnation, and you became a bat, are the lights still on? Do you have thoughts? A sense of self? What does sonar feel like compared to sight or sound? To clarify, the only reason I chose bats, is that it was the topic of a famous 1974 essay by Thomas Nagel of consciousness — one of the great remaining mysteries of science.

What is consciousness, exactly?

Well, we don’t exactly know. We know that when we sleep, we don’t have it. Except in dreams. When we zone out on the highway, we have less of it. Most definitions of consciousness include things like self-awareness and the qualities of our experience, or “qualia”. Things like the redness of the color red. Not only can you have emotions, but you can be aware of your experience of emotions and their subtle internal qualities. It’s the movie of our life that never stops. Well, through meditation it is possible to momentarily pause this internal movie, and experience a state without an inner subject as part of the experience, where just the raw inputs of life are present without introspection or judgment. This can be associated with a loss of self.

When you go to sleep, with or without dreams, there is an interruption of your conscious experience. In some sense, it is a little death. With modern physics, we know that all the particles making up your body and brain are just excitations in a field, and therefore in constant if minute flux. You are a pattern of energy, in a real sense. These two ideas give credence to the claim that the person waking up truly is not you. In fact, you never were you. There is no you. Each morning a new being emerges, gaining consciousness, armed with memories of a past being. Every day truly is your last!

One simple way to understand that concept of discontinuity is amnesia. Most of us have never had clinical amnesia, but perhaps a night or two of heavy drinking. Since you have no memory of those events, often negative, you can mentally divorce yourself from those events by stating that’s not me. There are many documented cases of loss of short-term memory from brain damage, where there is a continuous loss of a sense of self due to not having any recent memory as a reference.

So if consciousness is never continuous, can we really die at all? Well, if nothing else, it seems hard to imagine the atomic structure that represents your memories in your brain staying intact. When the matter dies, the possibility of reviving a conscious being dies. Later on, we’ll revisit this idea, but for now, for most people, the idea of a clone, robot, or simulation encoded with your electrical brain patterns doesn’t quite feel like a life worth living. Well, at least it’s not your life anymore.

So let’s go back. There’s a thing called consciousness. We can point our finger to it subjectively. We all have it, supposedly. Where is it? Is that a question that can be asked?

Is consciousness in the brain?

Everyone has a mental image of the human brain, with the wrinkly bits on top. That’s your neocortex, which is the thinking brain. Below that, you have all manner of smaller parts that we inherited through evolution from mammals and reptiles. The oldest part being the brainstem, which controls our autonomous functions like your heartbeat and digestion. So which are the conscious parts? Well, we know that some parts seem to display very little activity related to consciousness, and others quite a lot. The cerebellum controls motor functions, seemingly unconsciously. That’s how you can catch a baseball without being aware of the necessary muscles required for the precise timing and motion. From brain trauma and animal testing, we can deduce some specific characteristics of the main areas of the brain.

Certain parts of the newer primate neocortex deal with planning and sensory models of the world, while emotions and long-term memory are controlled by the mammalian limbic system. It seems that conscious experiences often involve interplay or feedback between planning, memory, models, and emotions. All of these can be shown to have value in survival and reproduction as evolutionary drivers. For example, emotions are a form of future reward. If something makes you sad, you can form a persistent memory of that sadness that you wish to avoid in the future.

There are many formal models of consciousness, including the Higher-Order Theory of Consciousness. It seems to say that the entirety of consciousness happens within different parts of the neocortex, with feedback loops from the sensory cortex to working memory areas. The key is that you are only conscious if you have a representation of your experience. It’s not enough for your neocortex to receive a visual stimulus of seeing a red balloon, you must have a specific representation of seeing a red balloon to be conscious of the experience.

The Global Workspace Theory of Consciousness positions conscious activity as arising from working memory much like the desktop on your computer. You are only aware of what’s on the desktop, not all the thousands of files on your entire computer at any time. Consciousness is therefore presented as a function of access to representations in your brain. Representations can be sensory, abstract, or from memory.

Older theories place all of consciousness in the emotional circuits within the amygdala, part of our reptilian limbic system. Another yet connects arousal from the brainstem with general awareness from the insular cortex and anterior cingulate cortex, effectively stating that our intelligent planning mammalian brain is controlled by our reptilian brain.

If these seem a little vague and functional, then there’s another new theory to weigh. Famous physicist Roger Penrose and anaesthesiologist Stuart Hameroff have pinpointed a specific structure within brain cells as the potential source of consciousness. But not just regular, boring consciousness. This is quantum consciousness. Queue the X-Files theme song.

There are truly minuscule, nano-scale structures inside brain cells called microtubules. They are in fact so tiny, and so structured, that they could allow for quantum effects like entanglement and tunneling between groups of neurons. This could solve another great mystery in the role of the observer in quantum wave function collapse. Consciousness then becomes functional in giving us a macro-scale universe that seems deterministic and void of quantum effects. Oh, and it might explain free will, too. Because quantum entanglement would allow your neurons to react to stimuli faster than neurons can fire, i.e. travel back in time a few milliseconds to decide what to do. It’s all pretty fantastical, but still scientific. While some quantum effects have been detected in microtubules, several aspects of the theory have been disputed by experimentalists.

So the jury is out. The one thing we do know is that neurons are the only cells that do not effectively regenerate in your body. All other cell types regularly get replaced, to where every 7 years you effectively have all new cells. But you’re pretty much stuck with the brain cells you were born with. Synapses change constantly, but neurons don’t. That might tell us something about consciousness already, in that messing with the structure would be a bad thing for the function of the brain which clearly includes consciousness.

Is consciousness the meaning of life?

It’s easy to make the leap from attributing consciousness, of some form, to all living things, to seeing consciousness as a requirement for life. But let’s remember, cells are alive. Are cells conscious? Are cells intelligent?

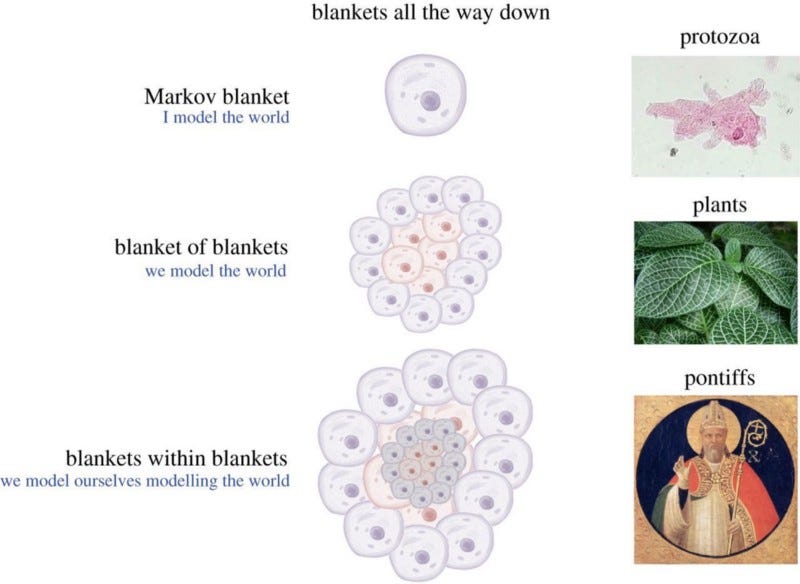

Philosopher Karl Friston asks us to consider a drop of oil. Is it alive? No, of course not. But what exactly is the difference between a drop of oil and a cell? Both have a physiological boundary, called a Markov blanket. Both are actively sampling the environment, otherwise, oil would mix with water, yet it never does. Well, the difference is actually in motion. The drop of oil can only move in reaction to external forces like pressure and gravity, but never cause movement from an internal process. The cell can move thanks to its ability to ingest and expel energy.

Humans are made of living cells, that seem to produce consciousness when assembled in the right pattern. We would certainly be alive without consciousness, but would such a life carry any meaning? Does a Roomba robot really care if it is turned off? It seems not. Clearly, there is some evolutionary driver to proliferate consciousness, as it seems abundant to varying degrees in animals. Perhaps, it is fair to say, that consciousness attaches meaning to our lives. We can experience, we can feel, we can hope, we can dream.

So we all have it, we can play around with it a little, and it’s all in the brain. Wonderful. Who even cares? It just is what it is. How is this going to affect my life?

Why consciousness matters

There are many reasons why you might care about consciousness. One is certainly the practical matter of morality. Euthanasia can be considered morally acceptable for people in irreversible vegetative states. Yet it would be considered murder for a conscious human. So it matters a lot. Babies used to be circumcised without anesthesia because we didn’t attribute real human consciousness to babies. Crying was just an instinct. Babies hadn’t yet developed the capacity for consciousness, was the thought, because they lacked language, memory, and motor control. If we now admit that babies can have a meaningful conscious inner experience, where is the line drawn? What stage of development from egg to fetus to baby is that line? What about animals? Are chickens being slaughtered for food conscious? What about cows?

The other reason is more philosophical but highly subjective in nature. What role does consciousness play in our development? Are we human because we are conscious, or conscious because we are human? Why is it like this to be human at all? What does it mean? Is consciousness the meaning of life? If there is other intelligent life out there in the universe, should we assume they are also conscious? If we develop real artificial intelligence, beyond human intelligence, will it be conscious? Does it matter, if it isn’t? What happens when you die, and could you come back like you wake up from sleep if the tissues were somehow preserved?

Okay fine, we have questions, but what’s the real mystery or problem here?

The hard problem of consciousness

Well, think about it. The brain developed an incredible capacity for intelligence and social interaction through evolution and has been spectacularly successful in proliferating the human genome. That’s fantastic. We have all the necessary functions for physical and mental dominance over all other species of the Earth. Perhaps you’ve never stopped to ask a simple question. Why is there any inner experience at all?

Why do we need any qualities attached to our experience? Couldn’t we perform all the same tasks of being a functional human, like… a robot? If there is pain, why do we need to suffer? Couldn’t we simply learn to not do that without the visceral quality of pain? Why do we need regret, longing, and love? Couldn’t we have evolved with all the same behaviors, without attaching quality to any of it? Like a Vulcan from Star Trek.

If you struggle with this distinction of function vs. quality, just think about other forms of life, and what you could say about their inner experience of life. Your dog, is it conscious? Probably you’d think yes, they seem to have rich inner experience, even if they cannot tell us about it. Cats, yes, but perhaps a little less so. Hamsters? Fish? Flies? Worms? Bacteria? Coronavirus? For most people, the buck stops around fish and reptiles. They seem to just… be, without much fuss about being or not being. You don’t see fish playing, or displaying anything that humans might interpret as subjective experience. Dolphins and whales do, but they’re mammals.

Wait, isn’t this just intelligence?

Okay, so fish aren’t particularly intelligent. Is a Roomba robot intelligent or conscious? Maybe neither. What about AlphaZero, a computer program that beat all humans in Chess and Go? That seems super-intelligent, but surely not conscious? Well, you might say that AlphaZero does not have a similar kind of intelligence as humans. It plays a few games at a superhuman level, but has no other functionality, even in terms of learning other tasks. It has learning and memory, but is there experience? It has models but no sensory inputs. It doesn’t see the game board or itself playing, it just sees matrices of numbers. So perhaps, there is a useful distinction between intelligence and consciousness?

One way to look at intelligence versus consciousness is to consider the functional inputs and outputs. We perceive things through our senses, and that gets converted into electrical signals that travel to our brain. Similarly, other signals come out of our brain into our nervous system, which triggers actions like lifting your finger. Imagine if some evil doctor meticulously and deliberately disconnected all the nerves connecting your brain to your body, painlessly, during your sleep, and you woke up in the morning. Would you wake up at all, actually? Would this evil doctor need to reconnect all those nerves to artificial organs, for that to happen? Well, nobody has yet volunteered for this experiment, strangely. What we do know is that people who lose complete functions of their body in accidents often continue to report “ghost” sensory experiences. Yes, even people who go blind with no connection between eye and brain can report seeing things. The evidence that the brain is the source of your conscious experience is overwhelming, and the existence of a soul, outside the brain at least, seems all but impossible.

For millennia, this separation of soul and body was the leading belief among scientists and philosophers. It was further reinforced by religion and the church, as it served their view of the world and creation. It’s hard to blame them, as so-called dualism is rather intuitive. When your body is disconnected from service during sleep, your mind can still explore and play in dreams. Other forms of altered states of consciousness seem to reinforce this notion, such as out-of-body experiences, and hallucinations. However, current scientific experimentation places the soul much closer to the vest, most likely in your neocortex. Specifically, it is the self-model generated by the brain that gives us a sense of self that is at the core of our subjective experience. If there is no “I”, is it really an experience? You can momentarily experience such a loss of self through meditation practice. You can let go of this character of self, and be only conscious of raw sensory inputs such as physical feelings and sounds. You’re still conscious, but not in a way humans would think of as normal.

Unlike with intelligence that seems hard to pin down, we can easily find the limitations of our consciousness. Try thinking actively of some object like a cube, while paying attention to your breathing. Add listening to the sounds around you. Now add awareness of your legs. You can’t. Somewhere between 2–3 steps you drop off. You lose the first and at best must rapidly alternate between 2–3 items of awareness. So there is a limit to what you can be conscious of, at least with humans. It does open an interesting possibility for extending human consciousness, or artificial consciousness. Imagine being conscious of your entire body and its myriad functions at once. Imagine being conscious of the Internet? Could you imagine being conscious of an entire planet at once?

So it’s all information, and information processing? No special sauce, no biological goo, or soul?

Integrated Information Theory

The idea that consciousness is purely a function of information is called substrate independence. Meaning, it is not limited by our physical systems of the brain and body, but can be reproduced artificially in silicon or metal. This makes no claim that we know how to pull off such a feat, or that it will be easy, just that it is possible.

If we consider that intelligence is a function of processing between inputs and outputs, then does consciousness emerge from pure information processing? If we assume that’s true, couldn’t we actually formalize that processing some way? That is the attempt of Integrated Information Theory (“IIT”), which is a recent and initial attempt at a scientific, rather than philosophical, understanding of consciousness.

Most interestingly, it also proposes a way to quantify consciousness. It’s called Phi. More Phi means more consciousness. This important step has evaded all major attempts at defining consciousness thus far, so IIT presents a major opportunity for the field to proceed to experiment and validate hypotheses about consciousness.

The premise of IIT is to say that information with integration indicates cause-effect power, i.e. abstract concepts within the information are causally related. This could have an evolutionary basis through the requirement for fast responses to environmental stimuli. A tail in the bushes means nothing, but it implies a lion, which implies being eaten. Further, IIT says that all experiences have a corresponding structure in your physical brain. A specific pattern of electrical signals is the visual cue of the tail of the lion, and another is the fear of being eaten by said lion.

One major benefit of the IIT model is that it seems to explain the unconscious nature of the cerebellum, which has the most neurons of any brain section, yet has no correlated brain activity with conscious experiences. That’s that baseball catching part of your brain. Given you have 600 muscles in your body that fire up to 100 per second, it makes sense that a lot of bandwidth is required to learn and reproduce motor patterns. Think of a pianist in the climax of an energetic symphony. The pianist thinks in abstract representations like notes and timing, not finger movements. So the cerebellum is powerful, yet lacks the high degree of connectedness seen in the conscious neocortex. It’s lo-phi, pun intended.

Experimentation will have to show us how much of IIT can be attributed to intelligence, or function, over consciousness alone. Can you truly perform complicated tasks that require intelligence without any integration? Perhaps, this may be a clue that consciousness comes along for free when you get to higher levels of intelligence?

What does all this say about A.I.?

If information is the whole and only game in town, then you would think neural networks are relevant to consider. After all, they are rudimentary representations of how the neurons of our own brains work, as far as we know, that is. The great irony of A.I. is that we don’t know those artificial neurons work, either. Really. It works, spectacularly well, in fact, but we’re not sure exactly how or why. There seems to be some magical capability attributed to a network of simple arithmetic operations with non-linearity repeated thousands of times. The artificial brains don’t learn as broadly or as quickly as a human brain, but they still learn a lot. Just by showing lots of samples labeled with possible outputs, even a small neural network can learn very intricate relationships from input to output. Sometimes beyond human-level, even.

Currently, the major limitation of progress is around generalization. That means that if you learn one thing, you don’t need to learn every example to be effective in the real world. Babies don’t need to see all types of dogs to recognize a dog, but computers do. Humans can learn to play any type of game, from tennis to chess, but computers struggle to learn many things. They can be superhuman in one category, but the best we can do right now is learning across different Atari games or going from Go to Chess. That’s it. No tennis. No poetry. What’s missing?

Surprisingly few people are actively working on this problem. Most of the commercially viable uses of A.I. don’t require anything remotely like human intelligence. In fact, if you just need to control valves in a chemical plant, it’s better to not do a bit of sudoku or jazz composition on the side. Focused algorithms are incredibly useful commercially.

One of the few people actively thinking about it is Jan LeCun, one of the early pioneers of modern machine learning techniques in image recognition. His proposal is that Reinforcement Learning is the right path. For context, that’s the type of algorithm behind AlphaZero, for example. It’s learning by carrot and stick. If you do good, you get a carrot. If you do bad, you get a stick. That alone left to do lots of learning can produce spectacular intelligence like world-beating chess algorithms. So that gets us pretty far. What then?

Well, LeCun suggests we need a world view. A framework to represent the real world out there. For example, when humans play chess we see the pieces and the board. They are objects with context and meaning. The algorithm doesn’t see any of this. No shape to the knight. No color to the board. It just sees numbers. Knight D4. Checkmate.

The computer can learn the rules, but nothing about the objects. There is no meaning to moving a piece on the board, that can be reused in moving an apple. You might even argue, that even though the computer can play chess, it doesn’t understand chess. At all. To be precise, the computer can learn a function approximation that happens to have a strong correlation with good moves in chess. It’s not chess. If there was no human carrot and stick, it would in fact learn nothing whatsoever. The computer brain must be spoon-fed. This must change. The computer must be given a framework for modeling the world, just like humans. We understand deeply the environment we live in. How to move, how to find food, how to climb stairs, how to open doors, how to ask directions, how to hunt for jobs, how to write emails, and so on.

What if we got there? What if a computer could do all that? An exact functional replica of a human, but made from silicon and copper wire?

But are the lights still going to be on?

This comes back to our question of substrate independence. If you cloned yourself, which is technically already possible, then is the clone conscious? Seems that would be automatically true, even if it isn’t your consciousness anymore. It’s a copy. How far can you take that, though? If you just scanned your brain at the molecular or even quantum level into a computer simulation, would that be you, another copy of you, or just a virtual zombie lacking real human consciousness? Is a function approximation of the conscious behaviors enough to pass the test?

How can we know? When Alan Turing invented the computer during WWII, he already thought of this. He saw the evolution from a room-sized calculator to human-level intelligence, that it was possible. He came up with the Turing Test, which states that a human interacting with an entity in another room, solely through means of writing, should be able to discern whether this other entity is human or not. If they can’t, the result should be that the entity possesses human-level intelligence. So, chatbots then?

Already, claims have been made about passing the Turing Test with relatively simple algorithms. The usual tactic is to try to steer the human in a direction the algorithm can provide memorized answers in a human manner. But this never lasts. Given more than a few minutes, it breaks down eventually. We’ve all been there with Siri. Gradually, that will be pushed out further, with longer and more meaningful conversations that can be carried out by chatbots. Even if, again, they understand nothing of language itself. Yet much like with AlphaZero, a conversation is just one aspect of human intelligence. A hermit could have a rich inner life without stating one word while producing incredible intellectual or artistic feats. So how do we test for “real” intelligence or even “real” consciousness?

Amusingly, science fiction may have given us the answer decades ago. Blade Runner introduced the Voigt Kampf test, which was used to identify human-like cyborgs from the human population. Especially, when those cyborgs went rogue and violent. The test itself is designed to provoke emotional responses indicative of that special flavor of quality so key to the human experience. Difficult ethical and moral questions would be asked while measuring the pupil’s response as an indicator of emotional response. Kind of like a lie-detector test for the soul.

There is a fundamental problem with any such test though. This was shown by John Searle in his Chinese Room Experiment. It shows that an A.I. system can behave exactly as an intelligent, conscious entity should, but actually be utterly and completely clueless as to the contents of the experience it is having or part of.

Back in the world of today, we can also look at IIT for a measure of consciousness. The higher the integration of information, or Phi, the higher the consciousness, according to the theory. By design, simple feed-forward neural networks have a Phi of exactly zero, and cannot be conscious. There is learning but no integration. Yet more complicated networks such as recurrent neural networks or reinforcement learning can be shown to have positive Phi. That seems to imply that AlphaZero is conscious. It is doing a lot of integration of information, in fact. As much as a bacteria or fly? This we cannot yet say due to open questions in applying IIT and calculating Phi, but it seems very unlikely we should have immediate ethical concerns about Deepmind’s ethical treatment of AlphaZero as a conscious entity.

A.I. researcher Joscha Bach has gone as far as to state that only simulations can be conscious, implying that physical systems cannot. Note that since the brain simulates the world and self, our consciousness would fall under this definition of simulation, while a rock would not. This would be an argument against panpsychism, whereby consciousness is everywhere in the universe, just to different degrees in all matter. AlphaZero does model the world but does not really model itself, so it might fall short here for now.

Couldn’t this just all be emergent phenomena?

Let’s go back to the only conscious beings we can be certain about, namely ourselves. We know about evolution. Couldn’t this all just be explained away as emergent phenomena from how our brains evolved? Ants may not have the capacity in neurons to have regrets about the-one-that-got-away, but we do. Maybe suffering and regret are what got us here. Our brains developed relatively rapidly once fire and weapons allowed us to congregate in larger social groups. If you learn to suffer, you can learn to avoid a broad set of behaviors that may lead to the ultimate suffering in death itself. Intelligence allows you to regret in hindsight, and plan into the future to avoid potential sources of regret. It’s all very nuanced, but the intricacy of human interaction is endless.

But then how in the world did we develop all this nuance? How can the brain produce such incredible deep complexity out of monkeys beating each other with sticks? If intelligence and consciousness are so closely linked in human evolution, then how does it work inside our brain? Well, sadly, we don’t know that either. Given how much we’ve done with our brains, from General Relativity to the Human Genome Project, and going to the moon, we seem to know incredibly little about the source of all this intellectual progress.

We certainly know the parts of the brain, what some of them are functionally related to, how they evolved from lesser species, and we can measure brain activity as electrical signals between parts of the brain. That’s it. We have no idea about how learning works, for example. There is no human learning algorithm, even though we can now teach neural networks to beat us in chess. Part of it, of course, is our limited moral capacity for experimentation. Hannibal Lecter wouldn’t get many research grants. The other is just the sheer complexity of the system. There are more neurons in one human brain than stars in our galaxy, and that’s around 100 billion. Each neuron is connected to another 10,000 neurons. It boggles the mind, pun intended.

One fascinating novel approach to unraveling the relationship between the inputs and outputs of the brain is the Thousand Brains Theory. According to this framework, we don’t have a brain. Instead, we have thousands of little brains, that are connected. These are the so-called cortical columns that are somewhat self-contained stacks of neurons, that include a special type of neuron called a grid cell that interprets spacial information. No one column ever does anything alone.

The idea is that you have hundreds or even thousands of these units receiving the same signal, like in the visual cortex. Then they all produce an output of some sort. They vote. Yes, vote. This is why you can know there is a floor underneath the rug, without having to see it. Your brain can use a variety of sensory and memory inputs to estimate three-dimensional objects, like mugs. That’s how you know exactly where to place your fingers to reach and hold the backside of the handle.

This model (B) is very different from the traditional model (A) that has also inspired current Deep Learning techniques. Deep Learning assumes a hierarchy of connected layers of neurons, each responsible for higher levels of detail resulting ultimately in a decision or recognition.

Maybe this is why babies are so excited about peek-a-boo, since their thousand brains haven’t yet acquired memories to say what happens behind the curtain of the hands, and they genuinely believe you disappeared behind your hands. This works for dogs, too. Maybe that’s why babies are clumsy. Their thousand brains are still practicing this choir performance of voting in real-time to produce the right actions.

This whole thing sounds like hogwash

Well, many leading scientists would agree. Consciousness has always been a bit of a fringe science between philosophy, psychology, physics, and neuroscience, without ever becoming a serious topic of study. Until now, perhaps triggered by the rapid evolution of artificial intelligence, and increasing ethical questions about the treatment of animals. We need answers to these questions, and the pressure is mounting.

Yet many, such as professor Sean Carroll would simply say there’s nothing special going on. Wallace has said there is no physics of digestion either, it’s just biology, end of the story. Yet even rather outlandish concepts like Panpsychism are gaining some ground, presenting consciousness more as a force of nature like gravity, than a mere biological function. In that scenario, even rocks are conscious, just… less so.

The future of consciousness

So what’s the end game here? It’s a whole lot of reading and terminology you’ve suffered through to get here. Let’s close out with something juicy.

Apparently, a young Elon Musk came to the conclusion that the meaning of life is to spread consciousness across the universe. This is why it is our prerogative to explore the moon, Mars, and beyond. To seed the universe with the gift of life and consciousness. The human panspermia. This is especially true if there are no aliens out there, as the Fermi Paradox seems to suggest. It’s up to us to be the champions of life in the universe.

So what plans does Elon have for our consciousnesses? Well, he wants to tinker with them a little. Like, introduce a tertiary layer. Meaning the internet. Possibly with A.I. too. Oh, there’s a catch. It involves needles. But don’t worry, a robot will insert thousands of micron-scale electrodes into your neocortex. Super carefully. Only an inch deep or so. Oh, also the batteries. We’re gonna need to take out a bit of skull. No big deal, you won’t miss it, honestly. Like a coin size bit. Basically the brain jack from The Matrix, but maybe under general anesthesia. Not something you want to be conscious during.

Initially, like with most of Elon’s grand plans, the R&D will be funded through commercial use-cases. This is a great lesson for any entrepreneur. In this instance, that means curing brain conditions like Alzheimer’s, epilepsy, autism, or blindness. Yes, curing blindness is on the menu in 2020. These are all major societal problems and therefore billion-dollar opportunities. It will directly help millions of people with debilitating health conditions while funding the real vision of a tertiary layer of the brain for healthy people.

So what’s Elon’s stance on the C-word? Elon would fall into the emergence camp. Everything from 0 and 1. No special sauce. If you can fix the TV by kicking it, you can fix the brain by zapping it through those electrodes. That’s it. Get your eyesight back, stop those seizures. But those electrodes can also download. Your thoughts, your memories, your emotions. Backed up to the cloud. First via USB, then wireless.

From there, he proposes maybe you can even restore. Just like your phone or laptop, when it goes whack. Restore from the latest backup. Good to go. Want to erase a few awkward memories from last night? Swipe right. For the small step for mankind from there to literal immortality, all you really need is a new biological substrate. Say, like a clone.

The trillion-dollar question is this: is it you though? I mean, maybe it strokes your ego if a clone picks up where you left off, but “you” would still be dead forever. The difference here is that between sleep and death. You feel like the same person after sleep, but death is a one-way ticket. If we can’t really tell the difference, does it matter to you personally? Obviously, the clone that wakes up would totally say they are you with all your memories intact. But is that the same you waking up in a new younger hotter body, or just a clone with your memories?

Sooner or later, we may all have to make our own judgment.

Aki Ranin is the founder of two startups, based in Singapore. Healthzilla is a health-tech company and creator of the Healthzilla health analytics app (iOS) (Android). Bambu is a Fintech company that provides digital wealth solutions for financial services companies. You can follow me on Twitter.